I cannot recall what Rosemary Sutcliff thought about or indeed knew of Richard III— last week it was reported his remains will now be re-buried in Leicester Cathedral, his skeleton having been found under a car park in Leicester City. Over 500 years ago Sir Thomas More was not over flattering.

Richard, the third son, of whom we now entreat, was in wit and courage, equal with either of them (his elder bothers); in body and prowess, far under them both; little of stature, ill-featured of limbs, crook-backed, his left shoulder much higher than his right, hard favoured of visage, and such as in states called early, in other men otherwise; he was malicious, wrathful, envious and from his birth ever froward*. It is for truth reported, that the duchess, his mother, had so much ado in her travail, that she could not be delivered of him uncut; and that he came into the world with feet forward, as men be borne outward, and (as the fame runneth) also not untoothed.

[*Froward (sic): archaic word meaning difficult to deal with.]

- Source: Sir Thomas More, Richard III, 1515-16; first published 1557. Reproduced in The Oxford Book of Political Anecdotes, OUP, 1986.

In the Rider of the White Horse, the two Fairfax cousins speak about their grandfather being “a little bit King Richard’s man”. Sutcliff injects no note of disapproval…

LikeLike

Good to be reminded of that.

LikeLike

The book cover /may/ have been Rosemary Hawley Jarman’s “We speak no treason” which I think I’ve mentioned to Anthony before.

Scoliosis: Richard’s spine and mine look pretty much the same (apart from the fact that I have a steel rod holding mine together) so I have a kindred feeling for him. With his military training he was probably better supported from the worst effects of the curvature by strong muscles (and properly-fitted armour) but he was almost certainly in pain at least some of the time, from the pressure of uneven vertebrae against his nerves.

LikeLike

Thomas More was not Richard’s contemporary (he was a child when Richard died) and he was raised in the household of Richard’s most devious enemy, the scheming Morton which is where he received his information. More inverted the shoulders, showing that he was dealing with ‘passed on’ information…in fact it was Richard’s right shoulder that was higher than the left. How much this was known outside of Richard’s intimates was debatable, as such effects of scoliosis can be fairly easily hidden; no one mentioned it within his lifetime. Possibly his scoliosis became revealed when his body was stripped and flung over a horse; this would make the curvature become prominent (bending forward is a test for scoliosis.) More of course invented the withered arm, which is completely fictional, and Richard’s legs/hips appear even (although his scoliosis was mod. to severe, it was a C curve rather than and S and ‘well balanced’) so no limp either.

Interestingly, More wrote his ‘history’ several times, then left it unfinished and never published it himself…it is curious to think ‘why’ this might be. It was published after his death by family who also added to it.

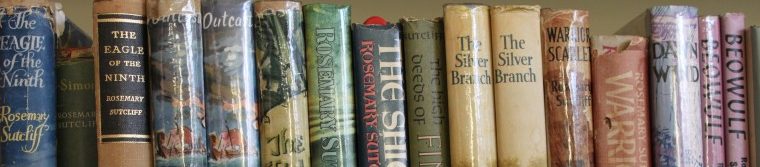

As for Rosemary Sutcliff’s opinion on Richard, I did once see a blurb on a book cover where she was praising a Ricardian novel. I somehow imagine she might well have given him a sympathetic treatment without being ‘fluffy.’ (I loved that her books were YA but never fluffy as you often see nowadays, no shying away from deaths or nastiness in a historical context…such as the girl killed and then buried in the pit under the horses, a scene that has remained in my head for many years.)

LikeLike

Intriguing about the book cover. And I too think she would have given him the non-fluffy treatment.

LikeLike