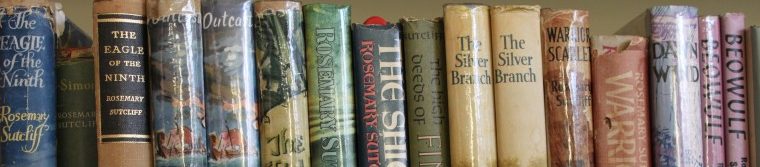

Acclaimed internationally for her historical novels and books for children, Rosemary Sutcliff (b. 1920; d. 1992) was the subject of many magazine profiles. Sadly she is no longer here to create pieces like the ‘This much I know’ feature in magazine of The Observer newspaper. But this much she did know, as revealed in her answers late in her life to Roy Plomley’s questions on BBC Radio’s Desert Island Discs.

A spinal carriage is like a coffin. It is very uncomfortable. You lie flat out in this ‘thing’, and all you can see the are branches of the trees or the roofs of the houses going by overhead. It is extremely boring.

I didn’t learn to read for myself until I was very old — I was nine before I could read. I think this was because my mother read aloud to me so much. Chiefly I had books read to me, which is a thing I love to this day.

I think it honestly never occurred to my parents that a child growing up and going through her teens required other young people. I was never allowed to bring friends home. They were very understanding; nobody could have had nicer parents. But they were very sufficient unto themselves.

Miniature painting is cramping. I was a good craftswoman—but I always had this feeling of having my elbows tucked too close to my sides when I was doing it. I gave it up to write. And I could write as big as ever I wanted to, I could use an enormous canvas if I wanted to.

I feel most at home in Roman Britain. I always feel it’s perhaps a little shameful to be quite so at home with the Romans, because they really were a very bourgeois lot, but I do feel very at home with them; I feel, ‘Here I am back at home again’ when I get back into a Roman story.

I think I do believe in reincarnation. I hope I do, because I think it’s the one thing that makes sense, that makes for justice and a really sensible pattern to life.

I can only create from the top of my head, down my right arm, and out of the point of my pen. So, I write in longhand.

I start with an idea; never a plot. I’m not very strong on plots, but I start from a theme, which grows from the idea. I do have a certain amount of framework: I’ve got to know how I’m going to get from the beginning to the end, and a few ports of call on the way.

I do not write to a standard length. I do not know how long a book’s going to be. I find that a book takes its own time and gets to its own proper ending place.

I take great pains that details should be right. I am quite shameless about writing to people—people who know about breeding horses, or whatever it is—and asking a particular question. People are usually very kind about sharing their own expertise. I do rely very much also on the feeling ‘does this smell right’, ‘does it have the right feel to it?’.

I don’t think I’m a particularly masculine kind of woman—although most of my books are told from a male point of view. I can’t write about girls from the inside. I don’t think the absence of sexual encounters is because I’m writing for children—I don’t honestly know why, it’s just happened that way.

I don’t know whose decision it was not to marry. The situation became impossible. My own family was so against it. People’s feelings were very different in those days to what they are now, about anybody with a disability being allowed to have any emotions. Neither of us were very grown up and we just couldn’t cope. So that was that.

Source: BBC Radio’s ‘Desert Island Discs‘.