Let us not be solemn about the death of Rosemary Sutcliff CBE, who has died suddenly, aged 72, despite the progressively wasting Still’s disease that had been with her since the age of two. She was impish, almost irreverent sometimes, in her approach to life. Her favourite author was Kipling and she once told me she had a great affection for The Elephant’s Child – because his first action with his newly acquired trunk was to spank his insufferably interfering relations.

But it was Kipling’s deep communion with the Sussex countryside and its history that was her true inspiration. Settled as an adult in Arundel, Rosemary shared with him his love for his county as well as his vision of successive generations living in and leaving their mark upon the landscape.

Rosemary Sutcliff, at the peak of her form in her “Roman” novels, was without doubt an historical writer of genius, and recognised internationally as such. Though most of her books were published for children, many – particularly The Mark Of The Horse Lord (1965), have about them the full stature and uncompromising treatment that make them valued additions to the bookshelves of historians.

Though she wrote more than 50 novels, set in times as far apart as the Bronze Age and the 18th century, her favoured period was the Roman occupation of Britain and the survival through it (survival is her theme song) of the native tribes. She writes hauntingly of the life of the Legions, the collapse of the Roman Empire and the carrying of the lantern of civilisation by the descendants of the early legionnaries into the Dark Ages. And it was in the Dark Ages that the Arthurian legends, her second love (surely not unrelated to the first?), were born. To the Arthurian legends which she retells in The Sword And The Circle (among other titles) for children and The Sword At Sunset (1963), an adult novel, she brings her own extraordinary narrative gifts and a touch of personal magic.

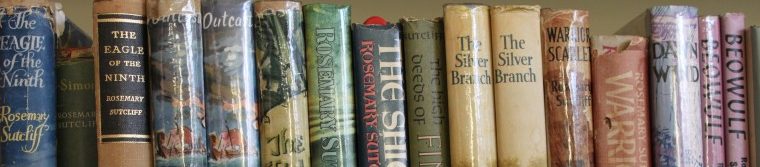

To the best-loved Roman stories – The Eagle Of The Ninth, The Silver Branch and The Lantern Bearers (winner of the Carnegie Medal) – she brings life, glowing and immediate, the result of painstaking research that fired an imagination of extraordinary richness. Song For A Dark Queen (1978) celebrated one of her rare heroines – Boudicca – and she was at once pleased and amused by its outcome, ‘The Other Award’, which is normally conferred upon more self-consciously anti-sexist authors.

Many of Sutcliff’s admirers are struck by the luminous details in her work that conjure up a palpable vision of a Northumbrian wood, a sleeping wolfhound, a young Roman soldier in the noise and mud and confusion of battle. They may not know that at the age of 14 Rosemary Sutcliff left school (“I was hopeless at everything – English, History, Nature Study, Latin – all the things that interest me now”) to study art. But few of those admirers will be surprised to discover that afterwards she became a miniaturist of distinction.

In Blue Remembered Hills (1982), a painful and moving account of her early life, she describes her six-year-old self sitting with her legs stuck straight out in front of her, investigating and experiencing “to my heart’s content the foot or two of world going on around me . . . The turf was not just grass, but a densely interwoven forest of thyme and scarlet pimpernel, creamy honey-scented clover and cinquefoil and the infinitely small and perfect eyebright with the spot of celestial yellow at its heart.” Here is the eye of the young artist feeding the pen of the future writer.

Rosemary Sutcliff’s own pen had to be “fattened” and cushioned so that her arthritic hand could guide it – yet in her heyday she wrote 1,800 words a day in her elfin script on a single folio sheet and she made no fewer than three hand-written drafts of every novel before she was satisfied. She had just finished the second one in the evening before she died and there are two novels awaiting publication.

She was a professional and a perfectionist in her every endeavour and like so many of her heroes, she rose above apparently insuperable drawbacks.

Source: The Guardian (London) July 27, 1992, p. 39 – Obituary ‘Chronicler of Occupied Brittania’ by Elaine Moss

I really tend to go along with pretty much everything that has been composed within “The Guardian newspaper on

Rosemary Sutcliff life and work (obituary) � ROSEMARY SUTCLIFF”.

Thank you for pretty much all the advice.Thanks for your time,Rena

LikeLike